This will become a numbered chapter to allow cross-references, but that entails renaming the chapter & figures files

The aim of this book is to blow your mind! Or at least to expand your imagination and take visual thinking to higher dimensions. But, just like kneading dough to make it more flexible before shaping and baking, or stretching your muscles before a race or starting your car before you drive, it is helpful to begin with some warm-up exercises, mental ones here.

In this book, I present a number of graphical methods, some novel, designed to help you understand multivariate data and models, particularly when the number of variables exceeds what can easily be shown on paper or on your screen. Visualizing these in higher dimensions relies on ideas from geometry like projection and other analogies, and some mathematical techniques to bridge the gap between our three-dimensional experience and higher-dimensional realities of data and statistical models.

To set the stage for this expedition and hopefully rouse your enthusiasm for this endeavor, I try to pave the way for multivariate thinking with a bit of history, a simple scheme (1-2-MANY) for statistics and data visualization, a parable of thinking in one more dimension, and a recent example of multivariate discovery.

The Magic of Graphs

There is a magic in graphs. The profile of a curve reveals in a flash a whole situation—the life history of an epidemic, a panic, or an era of prosperity. The curve informs the mind, awakens the imagination, convinces. — Henry Hubbard, in Foreword to Brinton (1939), Graphic Presentation

The graphic art depicts magnitudes to the eye. It does more. It compels the seeing of relations. We may portray by simple graphic methods whole masses of intricate routine, the organization of an enterprise, or the plan of a campaign. Graphs serve as storm signals for the manager, statesman, engineer; as potent narratives for the actuary, statist, naturalist; and as forceful engines of research for science, technology and industry. They display results. They disclose new facts and laws. They reveal discoveries as the bud unfolds the flower. — Henry Hubbard, in Foreword to Brinton (1939), Graphic Presentation

These inspiring words were written by Henry David Hubbard, the first Secretary of the US National Bureau of Standards (also known for modernizing the Mendeleev’s periodic table). They reflect the time in the early 1900s when appreciation for graphical methods was widespread and applications of graphical methods in science and popular writings had finally become mainstream, along with textbooks (e.g., Peddle (1910); Haskell (1919)) and college courses (Costelloe (1915)).

Yet, perhaps paradoxically, this period, from 1900–1950 has been called the Modern Dark Ages of data visualization (Friendly et al., 2015; Friendly & Denis, 2001). There were few new graphical innovations and, by the mid-1930s, the enthusiasm for visualization among statisticians had been supplanted by the rise of quantification and formal, often statistical, models in the social and biological sciences. Numbers—parameter estimates, and, especially, standard errors—were precise. Pictures were—well, just pictures: pretty or evocative, perhaps, but incapable of stating a “fact” to three or more decimals. Or so it seemed to statisticians.

The re-birth of interest in data visualization among statisticians was heralded by John Tukey (1962) in “The Future of Data Analysis”, where he issued a call for the recognition of data analysis as a legitimate branch of statistics distinct from mathematical statistics. His ideas for Exploratory Data Analysis, or EDA (Tukey, 1977) introduced a host of new graphic methods (boxplots, suspended rootograms, two-way table displays, etc.), which were soon implemented in new software systems. You probably know the rest—an explosive growth of new ideas for high-dimensional data and statistical models, machine learning methods, and so forth.

Graphic discoveries, 1900–1950

All the modern forms of data visualization—the bar and pie chart, line graphs and the scatterplot had been invented 100 years earlier. Now, in this period, roughly 1900–1950, graphical methods were used, perhaps for the first time, to provide new insights, discoveries, and theories in astronomy, physics, biology, and other sciences.

Three useful examples are:

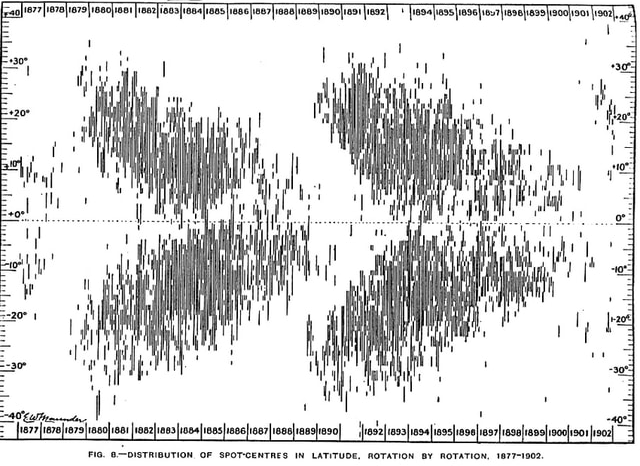

Edward W. Maunder (1904) plotted the occurrence of sunspots by their latitude over time. He observed a consistent, repeating pattern like the wings of a butterfies, with sunspots drifting toward the equator in 11 year cycles. This pattern proved crucial for understanding the properties of the Sun’s magnetic field.

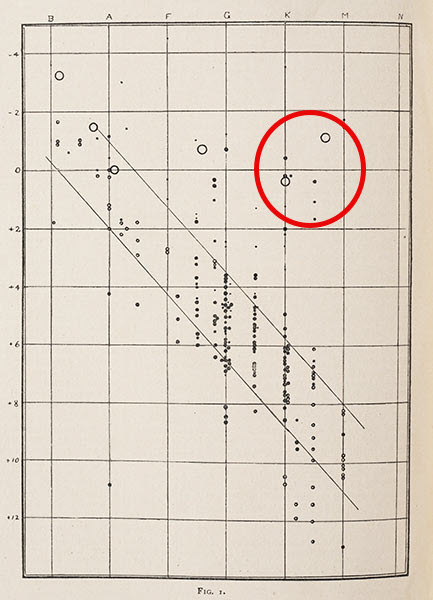

Ejnar Hertzsprung (1911) and Henry Norris Russell (1914) constructed plots of the luminosity of stars in relation to their color temperature and discovered an intriguing coherent pattern, but with a cluster of stars (“Red Giants”) detached from that main sequence. They used this to explain the changes as a star evolves. It provided an entirely new way to look at stars, and laid the groundwork for modern stellar physics and evolution. See Spence & Garrison (1993) for the full story of this graph.

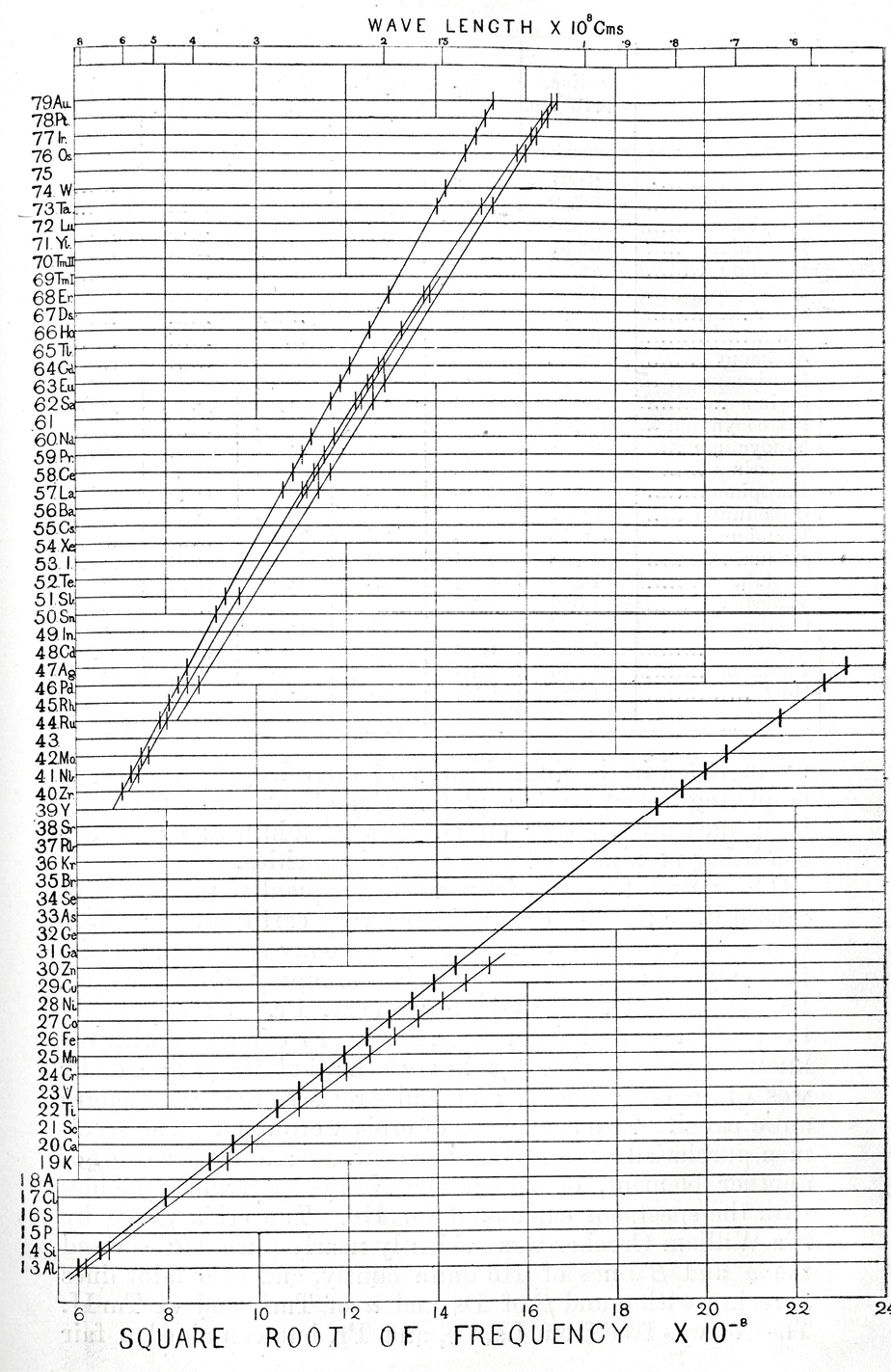

Henry Gwyn Jeffreys Moseley (1913) discovered, largely on graphical analysis, that the concept of atomic number (number of protons in an atom) rather than atomic weight (protons + neutrons = weight) gave a very simple theory of chemical elements. His plot of serial numbers of the elements vs. square root of frequencies from X-ray spectra showed a striking pattern of a series of straight lines. He noted gaps in the points and predicted the existence of several yet-undiscovered elements.

None of these graphs are particularly brilliant by today’s standards. They were all hand-drawn and rather crude. Yet in each case, something previously opaque became remarkably apparent in the graphic representation of data: a repeating pattern, some outliers departing from the rest, or the beautiful coherence of a set of linear relations.

ONE, TWO, MANY

To start thinking about the idea of “dimensions” of data and visualization, there is an old and helpful idea I learned from John Hartigan in my graduate days at Princeton:

In statistics and data visualization all methods can be classified by the number of dimensions contemplated, on a scale of ONE, TWO, MANY.

By this, he meant that, at a global level, all data, statistical summaries, and graphical displays could be classified as:

- univariate: a single variable, considered in isolation (age, COVID cases, pizzas ordered). Univariate numerical summaries are means, medians, measures of variablilty, and so forth. Univariate displays include dot plots, boxplots, histograms and density estimates.

- bivariate: two variables, considered jointly. Numerical summaries include correlations, covariances and two-way tables of frequencies or measures of association for categorical variables. Bivariate displays include scatterplots and mosaic plots.

- multivariate: three or more variables, considered jointly. Numerical summaries include correlation and covariance matrices, consisting of all pairwise values, but also derived measures from the analysis of these matrices (eigenvalues, eigenvectors). Graphical displays of multivariate data can sometimes be shown in 3D, but often involve multiple views of the data projected into 2D plots.

As a quasi-numerical scale, I refer to these as 1D, 2D and nD. This admits the possibility of half-integer cases, such as 1.5D, where the main focus is on a single variable, but that is classified by a simple factor (e.g., gender), or 2.5D where a 2D scatterplot can show other variables using color, shape or other visual attributes. John’s point in this classification was that once you’ve reached three variables, all higher dimensions involve similar summaries and data displays.

Univariate and bivariate methods and displays are well-known. This book is about how these ideas can be extended to an \(n\)-dimensional world. Three-dimensional data displays are now fairly easy to produce, even if they are sometimes difficult to understand. But how can we even think about four or more dimensions? The difficulty can be appreciated by considering the tale of Flatland.

Flatland

To comport oneself with perfect propriety in Polygonal society, one ought to be a Polygon oneself. — Edwin A. Abbott, Flatland

In 1884, an English schoolmaster, Edwin Abbott Abbott, shook the world of Victorian culture with a slim volume, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions (Abbott, 1884). He described a two-dimensional world, Flatland, inhabited entirely by geometric figures in the plane. His purpose was satirical, to poke fun at the social and gender class system at the time: Women were mere line segments, while men were represented as polygons with varying numbers of sides— a triangle was a working man, but acute isosceles were soldiers or criminals of very small angle; gentlemen and professionals had more sides. Abbot published this under the pseudonym, “A Square”, suggesting his place in the hierarchy.

True, said the Sphere; it appears to you a Plane, because you are not accustomed to light and shade and perspective; just as in Flatland a Hexagon would appear a Straight Line to one who has not the Art of Sight Recognition. But in reality it is a Solid, as you shall learn by the sense of Feeling. — Edwin A. Abbott, Flatland

But how did it feel to be a member of a flatland society? How could a point (a newborn child?) understand a line (a woman)? How does a Triangle “see” a Hexagon or even a infinitely-sided Circle? Abbott introduces the very idea of different dimensions of existence through dreams and visions:

A Square dreams of visiting a one-dimensional Lineland where men appear as lines, and women are merely “illustrious points”, but the inhabitants can only see the Square as lines.

In a vision, the Square is visited by a Sphere, to illustrate what a 2D Flatlander could understand from a 3D sphere (Figure fig-flatland-spheres) that passes through the plane he inhabits. It is a large circle when seen at the moment of its’ greatest extent. As the Spehere rises, it becomes progressively smaller, until it becomes a point, and then vanishes.

Abbott goes on to state what could be considered as a demonstration (or proof) by induction of the difficulties of seeing in 1, 2, 3 dimensions, and how the idea motion over time (one more dimension) could allow citizens of any 1D, 2D, 3D world to contemplate one more dimension.

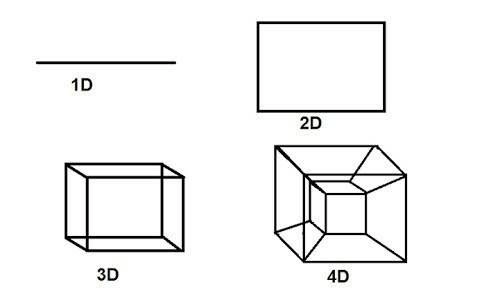

In One Dimensions, did not a moving Point produce a Line with two terminal points? In two Dimensions, did not a moving Line produce a Square with four terminal points? In Three Dimensions, did not a moving Square produce—did not the eyes of mine behold it—that blessed being, a Cube, with eight terminal points? And in Four Dimensions, shall not a moving Cube—alas, for Analogy, and alas for the Progress of Truth if it be not so—shall not, I say the motion of a divine Cube result in a still more divine organization with sixteen terminal points? — Edwin A. Abbott

For Abbot, the way for a citizen of any world to imagine one more dimension was to consider how a higher-dimensional object would change over time.1 A line moved over time could produce a rectangle as shown in Figure fig-1D-4D; that rectangle moving in another direction over time would produce a 3D figure, and so forth.

But wait! Where does that 4D thing (a tesseract) come from? To really see a tesseract it helps to view it in an animation over time (Figure fig-tesseract). But like the Square, contemplating 3D from a 2D world, it takes some imagination.

Yet the deep mathematics of more than three dimensions only emerged in the 19th century. In Newtonian mechanics, space and time were always considered independent of each other. Our familiar three-dimensional space, of length, width, and height had formed the backbone of Euclidean geometry for millenea.

However, the idea that space and time are indeed interwoven was first proposed by German mathematician Hermann Minkowski (1864–1909) in a 1908 lecture titled “Space and Time”.2 This was a powerful idea. It bore fruit when Albert Einstein revolutionized the Newtonian conceptions of gravity in 1915 when he presented a theory of general relativity which was based primarily on the fact that mass and energy warp the fabric of four-dimensional spacetime.

The parable of Flatland can provide inspiration for statistical thinking and data visualization. Once we go beyond bivariate statistics and 2D plots, we are in a multivariate world of possibly MANY dimensions. It takes only some imagination and suitable methods to get there.

Like Abbott’s Flatland, this book is a romance, in many dimensions, of what we can learn from modern methods of data visualization.

EUREKA!

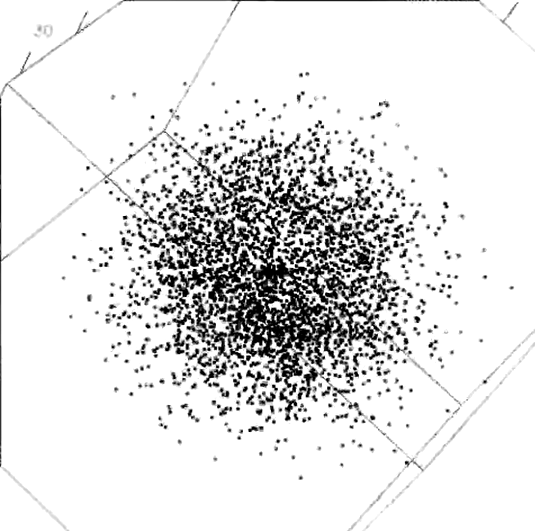

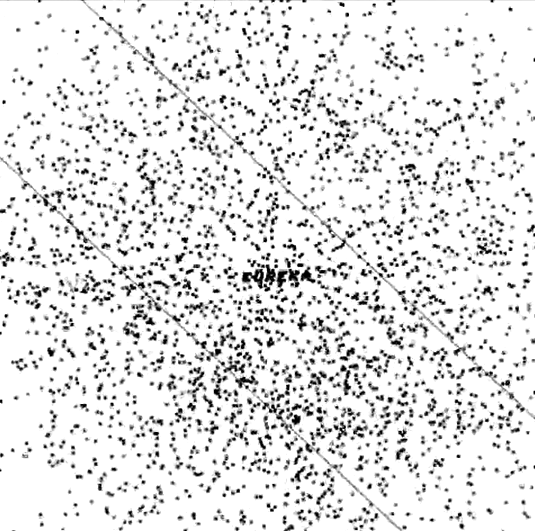

Even modest sized multivariate data can have secrets that can be revealed in the right view. As an example, David Coleman at RCA Laboratories in Princeton, N.J. generated a dataset of five (fictitious) measurements of grains of pollen for the 1986 Data Exposition at the Joint statistical Meetings, now available as HistData::Pollen.

The first three variables are the lengths of geometric features 3848 observed sampled pollen grains – in the x, y, and z dimensions: a ridge along x, a nub in the y direction, and a crack along the z dimension. The fourth variable is pollen grain weight, and the fifth is density. The challenge was to “find something interesting” in this dataset.

This problem is a case of searching for an unspecified needle in a five dimensional haystack. Those who solved the puzzle were able to find an orientation of this 5-dimensional dataset, such that zooming in revealed a magic word, “EUREKA” spelled in points, as in the following figure which shows four successive magnifications of the data (clockwise, from the upper left).

pollen data, zooming in, clockwise from the upper left to discover the word “EUREKA”.

The path to finding the hidden word can be seen better in a 3D animation. The rgl package (Murdoch & Adler, 2025) is used to create a 3D scatterplot of the first three variables. Then the animation package (Xie, 2021) package is used to record a sequence of images, adjusting the rgl::par3d(zoom) value.

Show the code

library(animation)

library(rgl)

data(pollen, package = "animation")

oopt = ani.options(interval = 0.05)

## adjust the viewpoint

uM =

matrix(c(-0.3709192276, -0.5133571028, -0.7738776206, 0,

-0.7305060625, 0.6758151054, -0.0981751680, 0,

0.57339602708, 0.5289064049, -0.6256819367, 0,

0, 0, 0, 1), 4, 4)

open3d(userMatrix = uM,

windowRect = c(10, 10, 510, 510))

plot3d(pollen[, 1:3])

# zoom in

zm = seq(1, 0.045, length = 200)

par3d(zoom = 1)

for (i in 1:length(zm)) {

par3d(zoom = zm[i])

ani.pause()

}

ani.options(oopt)

pollen data to reveal the word “EUREKA”. This figure only appears in the online version.The vague idea of finding “something interesting” in high-D data was first posed by John and Paul Tukey (1985) as an exploratory visualization method they called scagnostics, short for “scatterplot diagnostics”. Wilkinson et al. (2005) made this idea concrete by defining measures of features such as “clumpy”, “striated”, “convex”, “skinny”, and so forth. These methods are implemented in the scagnostics and cassowaryr packages.

Another idea is to search through high-D data space for views or projections with interesting features, initially called projection pursuit (Friedman, 1987; Friedman & Tukey, 1974). Some modern methods for this are illustrated in sec-animated-tours.

Multivariate scientific discoveries

Lest the EUREKA example seem contrived (which it admittedly is), truly multivariate visualization has played an important role in quite a few scientific discoveries. Among these, Francis Galton’s (1863) discovery of the anti-cyclonic pattern of wind direction in relation to barometric pressure from many weather measures recorded systematically across all weather stations, lighthouses and observatories in Europe in December 1861 stands out as the best example of a scientific discovery achieved almost entirely through graphical means–– something that was totally unexpected, and purely the product of his use of remarkably novel high-dimensional graphs (Friendly & Wainer, 2021, pp. 170–173).

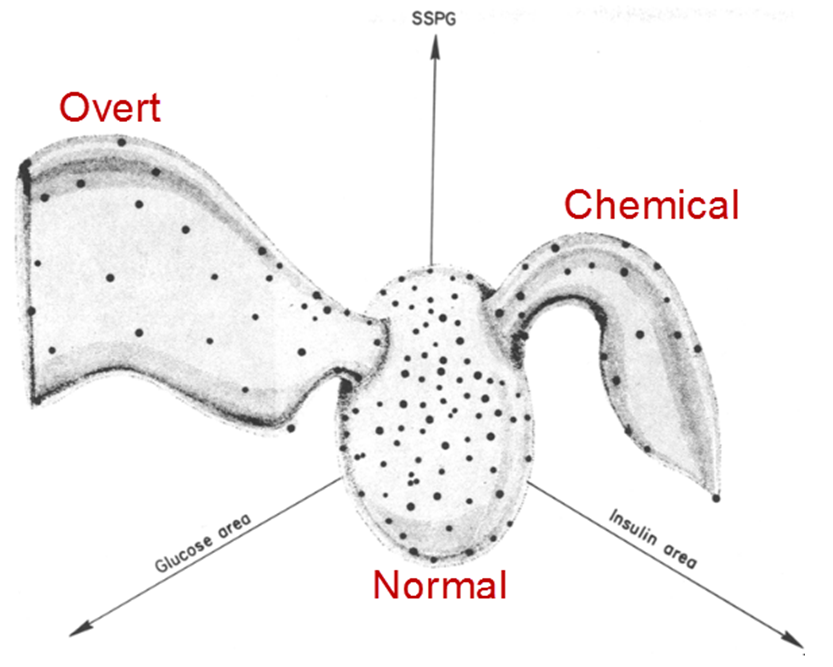

A more recent example is the discovery of two general classes in the development of Type 2 diabetes by Reaven & Miller (1979), using PRIM-9 (Fishkeller et al., 1974), the first computer system for high-dimensional visualization3. In an earlier study Reaven & Miller (1968) examined the relation between blood glucose levels and the production of insulin in normal subjects and in patients with varying degrees of hyperglycemia (elevated blood sugar level). They found a peculiar ‘’horse shoe’’ shape in this relation (shown in Figure fig-diabetes1), about which they could only speculate: perhaps individuals with the best glucose tolerance also had the lowest levels of insulin as a response to an oral dose of glucose; perhaps those with low glucose response could secrete higher levels of insulin; perhaps those who were low on both glucose and insulin responses followed some other mechanism. In 2D plots, this was a mystery.

data(Diabetes, package="heplots")

plot(instest ~ glutest, data=Diabetes,

pch=16,

cex.lab=1.25,

xlab="Glucose response",

ylab="Insulin response")

An answer to their questions came ten years later, when they were able to visualize similar but new data in 3D using the PRIM-9 system. In a carefully controlled study, they also measured ‘’steady state plasma glucose’’ (SSPG), a measure of the efficiency of insulin use in the body, where large values mean insulin resistance, as well as other variables. PRIM-9 allowed them to explore various sets of three variables, and, more importantly, to rotate a given plot in three dimensions to search for interesting features. One plot that stood out concerned the relation between plasma glucose response, plasma insulin response and SSPG response, shown in Figure fig-ReavenMiller-3d.

From this graphical insight, they were able to classify the participants into three groups, based on clinical levels of glucose and insulin. The people in the wing on the left in Figure fig-ReavenMiller-3d were considered to have overt diabetes, the most advanced form, characterized by elevated fasting blood glucose concentration and classical diabetic symptoms. Those in the right wing were classified as latent or chemical diabetics, with no symptoms of diabetes but demonstrable abnormality of oral or intravenous glucose tolerance. Those in the central blob were classified as normal.

Previous thinking was that Type 2 diabetes (when the body cannot make enough insulin, as opposed to Type I, an autoimmune condition where the pancreatic cells have been destroyed) progressed from the chemical stage to an overt one in a smooth transition. However, it was clear from Figure fig-ReavenMiller-3d that the only “path” from one to the other lead through the cluster of normal patients near the origin, so that explanation must be wrong. Instead, this suggested that the chemical and overt diabetics were distinct classes. Indeed, longitudinal studies showed that patients classified as chemical diabetics rarely developed the overt form. Our understanding of the etiology of Type 2 diabetes was altered dramatically by the power of high-D interactive graphics.

In his famous TV series, Cosmos, Carl Sagan provides an intriguing video presentation Flatland and the 4th dimension. However, as far back as 1754 (Cajori, 1926), the idea of adding a fourth dimension appears in Jean le Rond d’Alembert’s “Dimensions”, and one realization of a four-dimensional object is a tesseract, shown in Figure fig-1D-4D.↩︎

See the translation by Lewertoff and Petkov, “Space and Time Minkowski’s Papers on Relativity”, https://bit.ly/45NvgZR↩︎

PRIM-9 is an acronym for Picturing, Rotation, Isolation and Masking in up to 9 dimensions. These operations are fundamental to interactive and dynamic data visualization.↩︎